After Mount Augustus, I headed back to the heart of Goldfields country. With school holidays and the Easter break to contend with, I decided to stay here awhile and enjoy the hospitality of Kalgoorlie.

In case you didn’t guess, Kalgoorlie is famous for gold. Known as the ‘Golden Mile’ with good reason, in fact this is still one of the richest goldfields in the world!

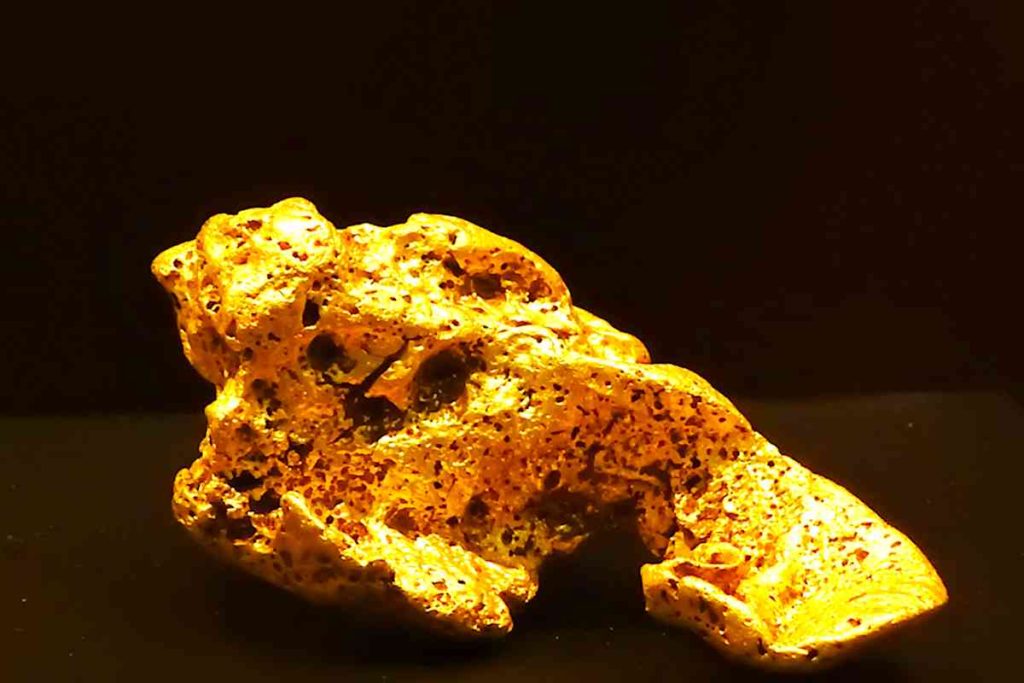

In town, at the Goldfields Museum, the aptly named ‘Vault’ displays gold in many forms for the poor people to salivate over. Showing various forms that gold is found in, the display has everything from chunks of gold bearing quartz to impressively large nuggets.

The well-heeled Kalgoorlie prospector had his finds made into gold Sovereigns and gold watches – coins and bling to display his success to the world.

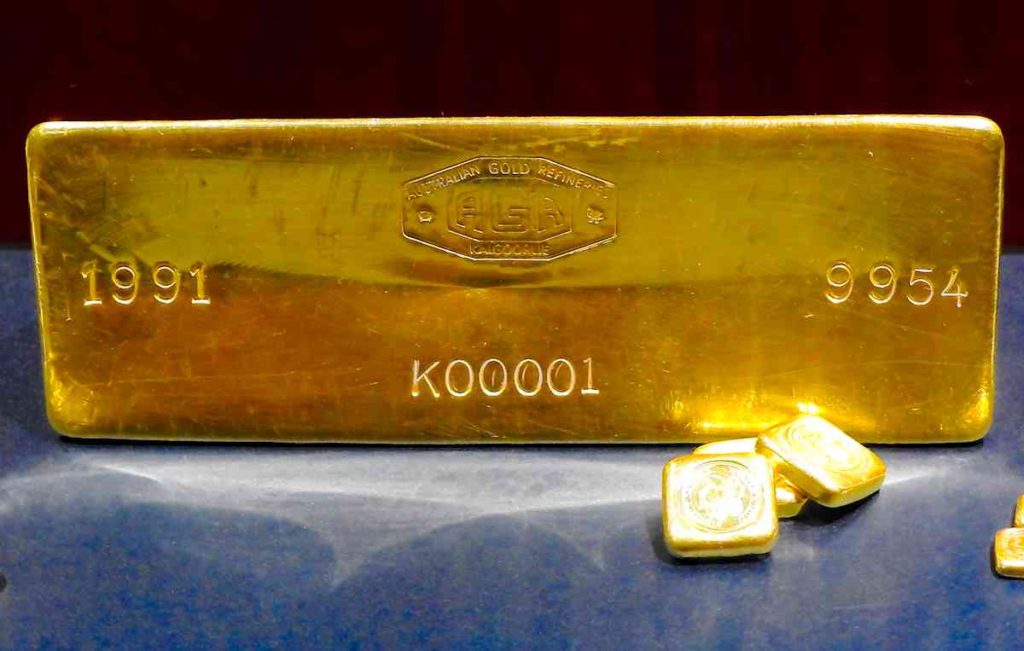

The prize of the Vault is a gold bar. Marked K00001, it signifies the first bar cast at the new Kalgoorlie mint in 1991. It is valued at $1.5 million although they reckon the gold value is only $850,000 (only???) Being the Number One gold bar apparently adds an extra dollar value!

Not surprisingly, all this gold is behind bullet proof glass, so you can look. But definitely no touching!

The amazing exhibits in the museum highlight our fascination with the lustre and wonder of gold. It also details the massively destructive nature of gold mining. Millions of tonnes of rock and dirt are required to scrounge a surprisingly small amount of gold and open-cut mining now scars vast areas of the countryside.

In the early days there were thousands of prospectors hoping to make their fortune. And, while there was no shortage of gold here, Kalgoorlie has no water.

Gold mining in the eastern states saw most gold in creeks or rivers, with plenty of water available for panning. Gold mining in this desert lead to special hardships; the foremost being how to pan without water!

Dry panning, where the wind was used to separate the finer dirt from the heavier gold was specialized here. Lack of water for hygiene led to outbreaks of disease and other, more mundane problems arose – the local newspaper reported the hotels could only serve raw whisky!

When a pipeline was built from Perth, it supplied much needed water to the goldfields. The vision of Charles Yelverton O’Connor, the pipeline became a reality despite vehement opposition from press and politicians. They argued it was a waste of money to spend money on a bunch of dirty miners, while seemingly ignoring the fact that gold mining was worth a vast amount of money to the WA economy…

O’Connor pressed on despite the disapproval and although he didn’t live to see the pipeline completed, he became a local hero. Opening in 1903, his pipeline still brings water to Kalgoorlie to this day.

Ghost Towns

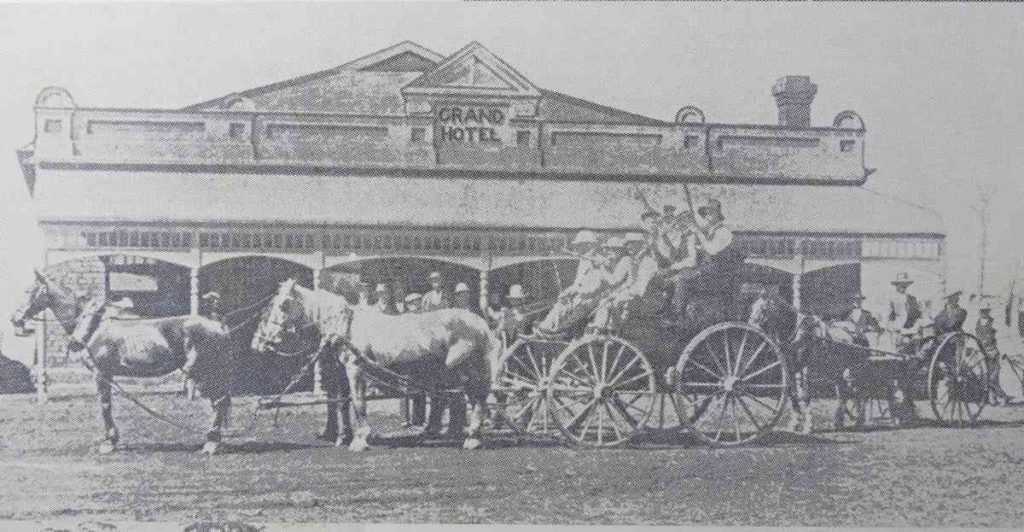

The country around Kalgoorlie is dotted with many ghost towns that attest to an opulent and vibrant past. One of these towns was Davyhurst, gazetted in 1901.

The town boasted three hotels, the most opulent being the Grand.

But when the gold ran out, people moved away and these towns died. Many of these abandoned places no longer display much physical evidence of their existence; you can only imagine…

I visited the ghost town of Gwalia, which in its heyday was a bustling town with a population of over 1,200 people. Gwalia is unusual in that many of the old buildings are still here, so you get a real sense of what it would have been like to live here.

Gold was discovered here in 1896 and The Sons of Gwalia reef gave its name to the town which grew up around the mine. The name reflects the Welsh heritage of the original owners and the mine has been one of the richest in Australian history.

The first mine manager was one Herbert Hoover, who later became President of the US. Hoover brought in Italian and Yugoslav immigrants to cut costs and to counteract the growing Australian labour movement. He was opposed to a minimum wage and workers compensation for the miners, feeling they were unfair to the mine owners. His bosses were obviously impressed; he was quickly made a junior partner!

Due to the numbers of immigrants living here, Gwalia was known as “Little Italy”.

Many of the old houses are still standing. You can meander around at your leisure, but people do still live here, so it is important to check you are not barging into someone’s home!

The State Hotel was built by the State Government in 1903 to combat the sly grog trade in the town. It must have done a roaring trade but in 1919 this hotel inspired a beer strike when 50 residents demanded the manager be dismissed. They were unhappy with the prices and the size and cleanliness of the beer glasses!

The hotel closed in January 1964 and was then derelict for many years. Now owned by a mining company, it is used as office space and accommodation, so you can’t go inside. From the outside it is still an imposing building, with a wide veranda providing welcome shade on the hot morning I was here.

The General Store provided a one-stop-shop for Gwalia residents for over 50 years. As with many country towns, you could buy anything you needed here, from soap to dynamite!

Many of the workers in the Gwalia mine were single men and numerous guest houses provided board and lodging for them. But only one guesthouse still remains standing.

Known as Patroni’s Guest House, a large kitchen and dining room catered for up to 28 diners at each sitting.

Very sparse rooms, built of corrugated iron, allowed up to 40 men to sleep in the shared accommodation.

With only hessian lining the walls between rooms, there would have been little privacy and it would have been very hot in summer.

Full board with meals cost £5 per week, which was a significant amount when you consider the average wage for a miner was around £7 a week.

When the mine closed suddenly in December 1963 there was a mass exodus from the town. The population of Gwalia dropped from 1,200 to 40 in around three weeks!

The mine has reopened several times and is now an open-cut pit. With modern mining techniques they are still pulling gold out of the ground here. They reckon that over the years Gwalia has yielded over 5.5 million ounces of gold, worth around $10 billion at today’s prices.